GAGOSIAN MAGAZINE SUMMER ISSUE 2019

LOST HIGHWAYS

Lee Ranaldo changed music forever when he, Kim Gordon, and Thurston Moore started Sonic Youth, in 1981. Here he speaks with Brett Littman, the director of the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, about his work as a writer and a visual artist.

BRETT LITTMAN: Lee, I wanted to start off with your relationship to writing. You’ve published several books of poetry and essays about art, music, and film over the years. When did you start to write?

LEE RANALDO: Well, I think I got interested in writing when I was very young, because I was an avid reader as a kid. I tried to write my first book at six or seven years old. I still have it somewhere in a box, with a cardboard cover, six or eight pages, a little tiny story with some illustrations. When I was a bit older, I went into a heavy science fiction phase and read Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, and Philip K. Dick. But it was probably reading Beat literature in my late teens that really turned me on to writing. Jack Kerouac opened the door to Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and all those other Beat writers. Their works sparked my interest in poetry, language, its sound, its texture, and what it could express. As well, listening to and reading rock ’n’ roll lyrics by people like Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison, and Patti Smith, who were consciously citing poetic references in their songs, made reading poetry more interesting to me.

BL: What made the Beat writers so important to you? Was it the kind of self-expression they represented, the stream-of-consciousness egoless writing, or just the musicality of their writing?

LR: I think it was all of those things that excited me. After high school, I spent the entire summer with my closest friend at the time traveling across the country in a beat-up old Volkswagen Bug. We had $300 each to our name and we went for two and a half months. It was unbelievable that you could do something like that then. We circled the entire country and spent a lot of time in California. So On the Road really knocked me out because I’d just seen all those American landscapes on my road trip and he totally captured that experience in his flow of the language.

BL: At some point you became friends with Ginsberg. How did that come about?

LR: Allen’s work was also very important to me, it just took me longer to appreciate how seminal he was to that whole scene. He was the survivor in that group—he lived a long life, never burned out, never stopped being a creative force and an intellectual giant. When I came to New York in the ’80s I had a chance at some point to meet him because I’d gotten involved with the Kerouac estate and had coproduced a record of Kerouac’s recordings. One of the things we found was a twenty- five-minute tape of Jack reading On the Road. It was amazing. Also, at some point I was the host of a Kerouac event in New York and I got to meet Ginsberg, Corso, and Ferlinghetti. I also did some performances with him. One memorable one was at St. Mark’s Church—I did a large ensemble version of his “Wichita Vortex Sutra” with Arto Lindsay, Philip Glass, and Steve Shelley from Sonic Youth. My other tangential connection to Ginsberg was that my wife, Leah Singer, actually lived in Allen’s old apartment, at 206 East 7th Street between Avenue B and C. This was the apartment where Ginsberg lived in the ’50s and where lots of photos he took of Kerouac and William Burroughs horsing around took place. It was also the site where Ginsberg shot the famous photo of Kerouac on the fire escape, with a brakeman’s manual in his pocket because he was working on the raiLR: oad at the time. The back cover of my first book, Road Movies [1994], shows me in that same position, standing on the fire escape just like him.

BL: Did you ever get Ginsberg to come and visit you at the apartment? I would imagine that would have brought back a lot of memories for him.

LR: When we first started to see Allen, we told him that Leah lived in this apartment. We kept trying to make plans for him to visit but we just never managed to put it together. There’s a funny video that Thurston Moore once sent me from a documentary on Allen that he filmed off his TV. In the documentary, Allen and Peter Orlovsky are standing in front of the building on East 7th Street and are buzzing the bell, saying, “We’re here to see Leah Singer and Lee Ranaldo.” Of course we’d moved out of that place several years before.

BL: Did you talk to Allen about writing?

LR: I did. At one point we got to talking about the language that he was using and he went into this long elucidation of the words and imagery in some of the poems. It was pretty insightful just to be next to him and have him explaining some of the ways in which he came to the language that he used. Also, he once asked to see my poems. I gave him a large sheath of the poems I was working on at the time. I know from others that he took a red pencil to them and marked them up, but sadly I never got them back. They’re among his papers, I guess.

BL: So what prompted you to start publishing your own writing?

LR: In the early ’80s, right at the same time that Sonic Youth started playing and touring, someone gave me a very early version of a laptop computer. It was this thing called the Tandy 102; it was marketed by Radio Shack and was the size and shape of a modern PowerBook. The only problem was it could only hold 32K of memory so it filled up quickly and then you had to offload what you wrote onto cassettes. When we were on the road I would sit in the van day and night and just write. Some people in the East Village saw some of these early things and this guy named Sander Hicks was starting this “punk publishing company” called Soft Skull and he asked me if he could publish me. That request made me get much more serious about my writing.

Lee Ranaldo by Max Zerrahn Berlin Oct 2017

BL: Your poetry is pretty conceptual, maybe a bit surrealist—you use lots of found text and e-mail spam as source material. How did that come about?

LR: I don’t know if you saw these e-mails but for a while, starting maybe six or seven years ago, my inbox would fill with these fake e-mails that were either for diet pills or penis enlargement. They slipped past the filters because they had reams of words at the bottom, as if a dictionary had exploded. Or there were excerpts from nineteenth- and early- twentieth-century copyright-free books—weird paragraphs about pirates and islands. I started collecting these e-mails because every five lines there’d be three words that were just like, “Wow, that’s as good as anything I’m coming up with right now.” So I began to cull these phrases and put them next to my own words and just started building these poems. They ended up seeming a bit surrealistic or free associative in their imagery. What I liked about this way of working was that I had an anonymous collaborator; the Internet was supplying me with reams and reams of this stuff. In some cases I even took some of it and just printed it out. One poem, “All the Stars in the Sky,” is all made from Internet words. I also started to use these texts in performative situations when I did solo things with my guitar but wanted to read, not sing.

BL: On Electric Trim, your new record, you collaborated with the author Jonathan Lethem to cowrite the lyrics for the songs. What inspired you to do that?

LR: I guess recently I was thinking about the period when Bob Dylan was writing that record Desire and he had Jacques Levy, a theater guy, cowrite lyrics. I thought, Who needs less help writing lyrics than Bob Dylan? Yet Dylan wrote a whole record in collaboration with this guy. It opened up his lyric writing to this whole other point of view. The other thing that inspired me to do this was my long-time interest in the Grateful Dead. I don’t know if you’re aware, but a guy named Robert Hunter wrote the lyrics for the great classic Dead songs. Hunter was a guy that Garcia had played bluegrass music with before the Dead started. He was more of a poet than Garcia so he became the in-house lyricist and was listed on the early records as a member of the band. The collaboration with Jonathan began when I was working on Electric Trim, which was produced by Raül Fernandez. I’d known Jonathan for a while through a mutual friend, and in 2017 he was coming to New York, so I asked him if we could meet to discuss the idea of collaborating on lyrics. He was immediately keen on the idea so we began to work on the lyrics for this record.

BL: What was the process like? Was it like a game of exquisite corpse, or did you use some other kind of method to collaborate?

LR: The writing process with Jonathan took all different forms. I started sending him instrumental music and said, “Here’s some of the stuff we’re working on. There’s no lyrics at all yet.” Then I’d send him stuff where I was like, “Okay, here’s a song, I need forty lines and I’ve got four.” The next day he’d send me an e-mail with the blanks filled in. One day he sent me a four-line couplet based on Edgar Allan Poe’s “Tell-Tale Heart” and “The Purloined Letter” that he’d had in his drawer for about twenty years and didn’t know what to do with. I was in the studio with Raül when that e-mail came in and those four lines immediately became the chorus of a song we were working on. There was one song in particular where I needed the last word for a lyric. We had a word but I didn’t really like it. He suggested three other words which then prompted a long discussion: how do you know when a word is the right word, is there a right word here or can any of these words work here. It led us down all these avenues of ways to talk about language and how people write and make sense of the language they’re constructing. It was a pretty interesting dialogue. In the end, some of the songs are dominated by Jonathan’s texts, some are dominated by mine, and some are totally collaborative.

BL: How did lyric writing work with Sonic Youth? I imagine it was a very different kind of process from the way you worked with Jonathan?

LR: Sonic Youth was very collective in the way it operated in terms of our music composition. When it came to lyrics, Kim, Thurston, and I all wrote our own lyrics for songs—although from time to time we occasionally crossed over and helped each other with lyrics and composing songs. Sonic Youth was a four-way democracy and we were all credited as songwriters because that’s the way we saw it.

BL: I’ve been listening to Electric Trim and I really hear it as a singer/songwriter album, like the kind that Joni Mitchell or Leonard Cohen used to put out.

LR: I’ve been solo for about seven years now since Sonic Youth stopped playing, touring, and recording. That’s allowed me to get more serious about songwriting on my own. I guess originally, I was looking back at singer/songwriters, these lone wolves, and they became much more valuable to me when I saw myself as a solo artist. This way of working, as opposed to being one person in a four-person band, has pushed me to move out of my comfort zone—I feel I’m restructuring how I work, and having a kind of renaissance and a new vision of what the future can hold. I want to do things from here on out that are more individualistic and less like everything else that’s out there, because that’s always what Sonic Youth was. We were like the sore thumb. We were not like anybody else.

BL: Can we talk about the collaborative work you’ve done with Leah?

LR: After my first book, Road Movies, came out, Leah and I did a few books together. We were always really big fans of and have quite a collection of books that marry image and text, like Marshall McLuhan’s The Medium is the Message [1967], where the pages are full-bleed pictures with text in weird fonts. We wanted to do a book like that ourselves. We did one in particular with a really small press called Bookstore. It’s Leah’s images for the most part, and my text, and we played with the text on the page and the way the text and the image met and bounced off each other.

BL: So the first collaborations you did weren’t musical, they were more in the realm of visual art. It sounds like you two were really thinking about images and texts in book form?

LR: Yes, that’s true, but Leah at that time was also using these analytical projectors and playing with improvisers in the East Village. Her film strips would have all these different things going on in them: pictures of flowers, Vegas lights, billboards. It was a bit like what DJs were doing with records. With those projectors she could freeze the image and “scratch” it, going superfast or very slowly, forward and backward. She would string ten of these short film clips together with black leader in between them, and each one of them would be a five- or ten-minute segment of visuals. Since she was also performing these films with other musicians when we met, it seemed only natural that we would work together. I think at first we just started by throwing something together—we were both fans of the idea that when you’re listening to a record and have the TV on with the sound down, there’s always pleasurable juxtapositions. So we started from that. We’ve now been doing these kinds of performances for a long time, and have really honed them down—no more analytical projectors, we work with video now—we had to get rid of those after lugging them across Europe on tour one too many times.

BL: Lee, can we talk about your own forays in visual art? I know you draw, are a printmaker, and also have made films. What do you find interesting about these mediums?

LR: Since the time I was really young, and to be honest it’s taken me a long time to figure this out, there were always three things that interested me: language, images, and music. I never really let go of any of those things, so they all kind of stayed in the mix in terms of what I do. Song lyrics, poems, and essays help me to explore language. I’m a printmaker, draftsman, painter, and filmmaker to satisfy my interest in image-making. I play guitar and perform because I love making music.

Lost Highway: 022418 to Tourcoing #3, 2018, colored pencil on paper, 12 x 9 inches (30.5 x 22.8 cm)

BL: How did the Lost Highway drawings come about?

LR: I was studying printmaking with Linda Sokolowski, a real master printer, at Binghamton. At one point we were learning the process of color printmaking and I needed to come up with imagery. A couple of months earlier I’d taken a road trip with a good buddy of mine and we drove down to Florida in a van that I had at the time. It was a late-’70s hippie road trip, you know, two-guysin- a-van-dropping-acid-in-the-Keys kind of trip. I started sketching in the car when we were driving and I made this drawing in Georgia called Route 95 Georgia. That ended up becoming the study drawing for this three-color print. Later, when I was on tour, I got a bit tired of writing journals so I started sketching more and it just led to this explosion of drawings. I drew all the time when I traveled and I started thinking about them in a diaristic way. I was in Europe, Texas, Iowa, India, and I was sitting in the front seat of the van drawing what I saw. This really sparked something in me and I became obsessed with this process. I made tons of these Lost Highway drawings in black and white with markers and pencils. I started carrying more and more drawing materials with me on the road. Some of them were sketchier and some of them were more resolved. I really liked this idea of the highway imagery because every musician has a road song. From Hank Williams on forward you’re always hearing about the lost highway. I was thinking about this idea of the musician’s lot and the road being a poetic image for a musician and for a writer.

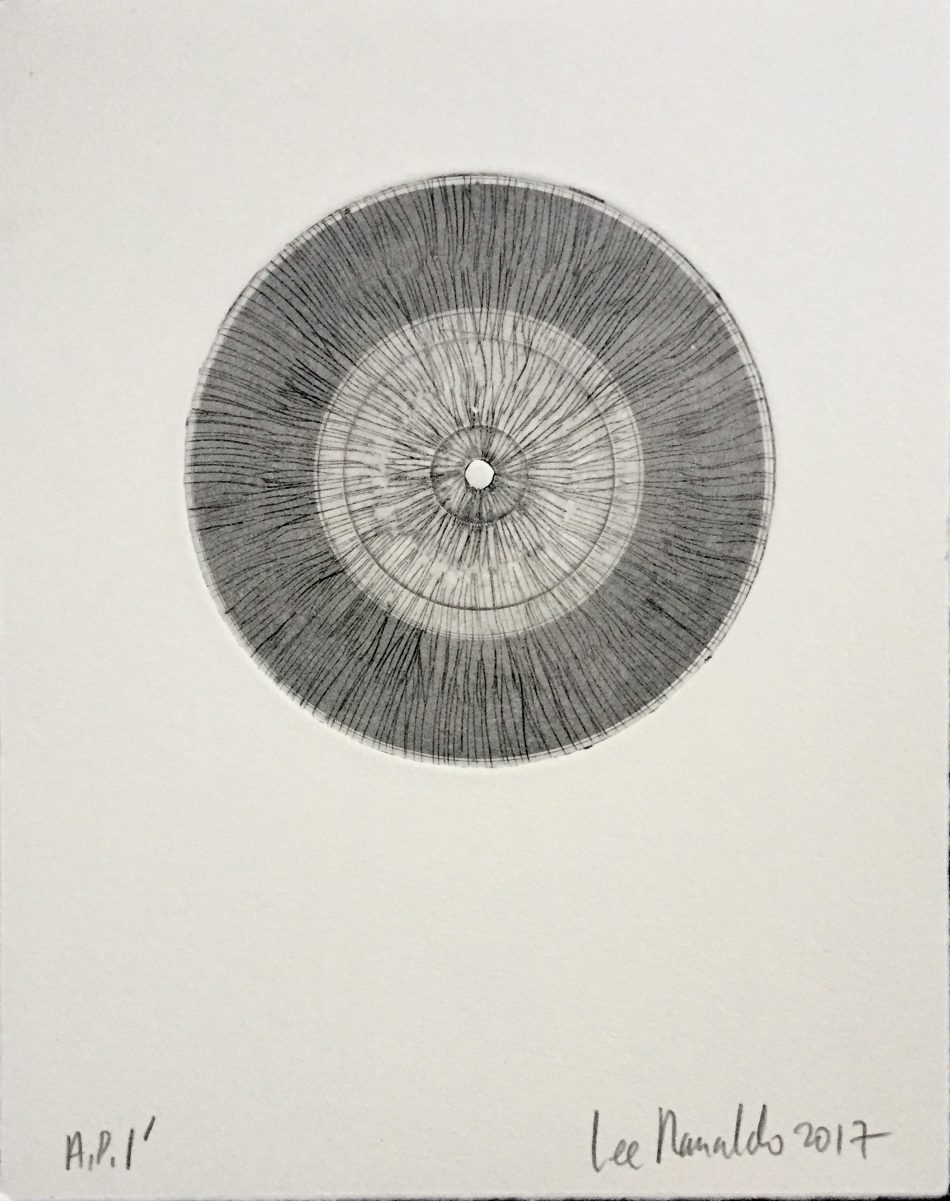

BL: You’ve also continued to make prints. I particularly like the Black Noise Record prints. How did you come up with the idea to use the record surface as a printing plate?

LR: After school, I didn’t have much chance to do printmaking because I was an etcher and you needed all that equipment to make a print. In 2007, Leah and I got invited to go to this small museum outside of Paris called Cneai. They had a great printmaking studio but since I hadn’t done printmaking in a long time, they wanted me to start off working on Plexiglas rather than on plates. The first summer we were there I was working a lot with newspaper imagery. Both Michelangelo Antonioni and Ingmar Bergman had died on the same day. I was ripping a lot of pictures out of papers and making paintings and drawings from them and reproducing the type and the texts. Later I ended up making small scratched Plexiglas plates with images of Bergman and Antonioni. After doing that I started to think about how vinyl records could serve the same function as Plexiglas so I just transferred to that medium instead. This led to this whole exploration of making prints on vinyl records. I found a bunch of sixteen- inch records that had been distributed to radio stations in the ’50s and ’60s. I also printed using twelve-inch, ten-inch, and those little sixinch records for kids. These are small editions because the vinyl doesn’t hold up for too long as a printing surface.

Black Noise: Mini C, 2017, drypoint on vinyl record, 12 1⁄8 x 9 5⁄8 inches (31 x 24 cm)

BL: Lee, I hope you don’t mind, but to end this interview I want to talk about some serious personal Sonic Youth nostalgia. In 1986, when I was in high school, my friend Tae Won Yu gave me a tape of Walls Have Ears. I don’t think I’d ever heard sounds like that. The performances were totally raw and the feedback loops and droning are totally hypnotic. I know that was a bootleg—what was the story behind that?

LR: In its original incarnation it was a double album. It was a bootleg done by Paul Smith, our label guy in England, who was really responsible for bringing us to a wider public in Europe. At some point in 1985 we arrived in England to tour and Paul proudly showed us the records. He was like, “I made this bootleg for you.” We were unhappy. We freaked out. We were like, “You didn’t ask us, you didn’t tell us, you didn’t consult us on what’s on it.” Of course, in the end he was doing it with the best intentions and out of utter love. One disc has Bob Bert on drums and one disc has Steve Shelley on drums, so it spans that divide in the band. At that time, we still felt like gorillas in a room. We were still very anarchistic. Everywhere we went outside of New York, people were just flabbergasted by our performances—they didn’t know anything like this existed. There was a brief period, and Walls Have Ears documents it, where we knew we were the most radical thing that people had ever seen. It was kind of amazing to us because people were freaking out at what we were doing. We were surprised because to us it was like that New York noise thing that we were all involved with. It was all no big deal. Everybody was experimenting, everybody was doing weirdo shit. You had the old guard like La Monte Young, Charlemagne Palestine, Glenn Branca, and a new generation of people like Arto Lindsay and DNA. Today that bootleg has become such a revered aspect of our catalog that recently we’ve been talking about doing a reissue of it because so many people love it and so few people actually heard the original or saw those shows—I mean we were playing to audiences of seventy-five people on the beach in Brighton, UK.

BL: That would be amazing. I hope you do rerelease Walls Have Ears, I’m sure that it would be a huge revelation. Everyone should hear those early performances. I know they were life changing for me!